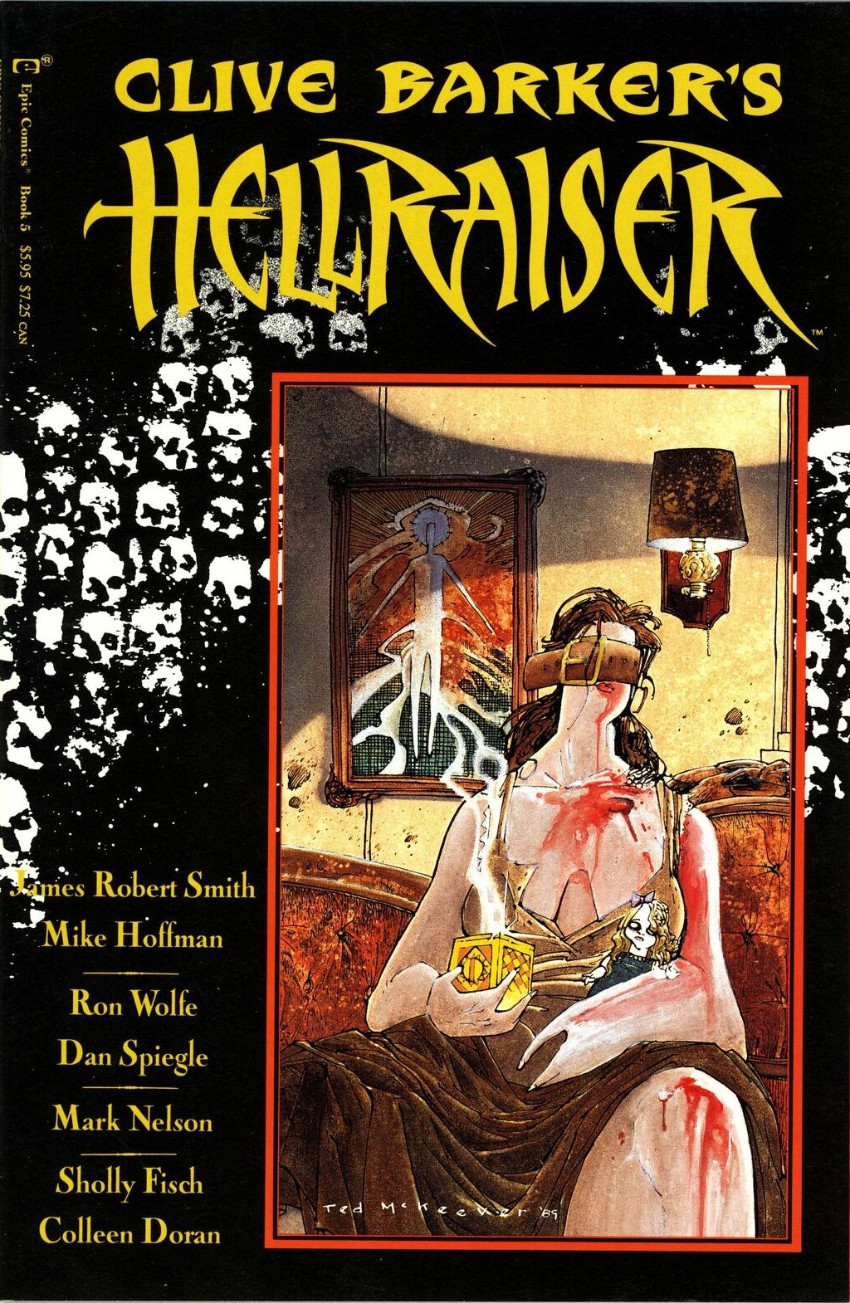

Doug’s blue eyes were covered with glassy black contact lenses to remove any trace of humanity and his skin was transformed to the mottled white of a corpse.īefore his first screen test, Doug spent 20 minutes alone in his dressing room, staring into a mirror and trying to make sense of his unrecognisable face. The novella describes the Hell Priest as a being of indeterminate gender, “tattooed with an intricate grid” across their head and face, with jewelled pins driven down to the bone at each intersection. The Cenobites themselves were inspired by 70s punk, Catholic iconography and Clive’s trips to S&M clubs in New York and Amsterdam, each marred with unique deformities and elaborate scarification, ranging from excised throats to mouths pulled open with hooks.ĭoug Bradley’s own iconic make-up took six hours to create. Like the story itself, Hellraiser’s aesthetics resembled nothing else in contemporary horror films.

The movie stayed relatively faithful to the original novella: the sadomasochistic Frank Cotton is sucked into a hellish dimension after summoning the demonic Cenobites with an ancient puzzle box known as the Lament Configuration, sparking murder, regeneration and a Faustian bargain with the Cenobites. “The context for me at the time was that it was another project to work with Clive,” Doug says. Doug had spent several years in a theatre group with the author, and whatever the latter was working on, he was game. He also called on his old friend Doug Bradley to play the lead Cenobite, officially named ‘Hell Priest’. Securing $900,000 from film company New World Pictures, Clive assembled a small cast, including Sean Chapman as the hedonistic Frank Cotton and Claire Higgins as his lover, Julia. “For me, was a chance to see if I could put what I felt I was putting onto the page onto the screen.” “The only way to do this was to write the novella with the specific intention of filming it,” he told Starburst magazine.

Having had two of his stories, Underworld and Rawhead Rex, mangled in transition to the big screen, Clive decided that it was time he tried his hand at directing a film based on his own work.

Whereas the likes of Stephen King and James Herbert were writing more traditional horror stories, the Liverpool-born author’s stories were an amalgam of dark fantasy, erotica and surrealist body horror. Clive Barker had burst onto the horror fiction scene in the mid-80s with his short story collections, Books Of Blood. (Image credit: Entertainment Pictures/Alamy Stock Photo )Īs the saying goes: if you want something done right, do it yourself.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)